DIGITAL MEDIA AT FRESNOY

by Dominique Moulon [ July 2017 ]

Le Fresnoy, France's international institution for the teaching, production and promotion of new media art, is a site for the digital contamination of images and sound. This is evident in the work of ten artists, some students and other teachers, who have been part of this school over the last decade.

Temporalities

Sébastien Hildebrand,

“Run Baby Run” , 2010.

“ W

“ Without

Le Fresnoy, I never would have had access to this technology,"

Sébastien Hildebrand says in discussing his photo suite Run Baby Run (2010). The "technology" in question is a high-precision measuring instrument used to decide the winner in sports competitions. Hildebrand worked with resident artist Hans Op De Beek to stages the scenes of women and men runners crossing the finish line. The he stretched out the time frame and flipped the background and foreground so that the former, although static, seem to be moving so quickly, ant that the figures seem to be frozen. These shots are punctuated by accidents — here and there a foot appears to be liquefied by oil under paint brush. "Photography has been, and still is, tormented by the ghost of painting," wrote Roland Barthes. It is Barthes to whom Hildebrand addresses his photos by comparing them to film shorts because of the short time spent they depict. He further specifies that they are in no way snapshots evoking "that which once was," again to quote Barthes, but rather fluidified fragments of female and male runners stretched to the extreme as they approach the finish line.

Nicolas Moulin,

“Grüsse Aus”, 2013.

T

The cities pictured in the series Grüsse Aus (Greetings From) that

Nicolas Moulin made for the 2013 show Panorama 15 while living in Berlin never really existed. "It is not down on any map; true places never are," as Herman Melville wrote. These are constructed mental images, like stage settings where no actor would never appear. This artist who emptied Paris of its people continues his effort to depopulate real and fictional worlds. In his work, reality and fiction can be found side by side, so much so that the views in the Grüsse Ausseries seem familiar. Extracted from some past to which they could possibly bear witness, or announcing possible futures, they nevertheless have nothing to say about the present. They do not document the provenance of the put-together fragments they are made of, since everything runs together in this time of a network-driven, constantly accelerating globalization. Moulin takes a lot of pictures of cities and their abandonment, but they are seldom bestowed the status of an artwork until after his interventions, often in the form of post-digital collage.

A Learning Curve

Bertrand Dezoteux,

“Le Corso”, 2008.

T

The work of

Bertrand Dezoteux, the winner of several prizes including tbe Audi Talent Award, is also situated on the boundaries between fiction and reality. He turned to making 3-D pieces at le Fresnoy in 2008 with the film short Le Corso, later acquired by the Aquitaine regional contemporary arts museum (FRAC). The fictional landscapes are computer generated, while the animals that are its seem like something out of a documentary. The audio track sounds like a real-life recording. The images themselves are testament to professional software while, conversely, the jerky movements make the camerawork look amateurish. The situations and dialogue are strange, to say the least. Some of this strangeness is due to accidental effects the artist chose to keep. "Pretty often it's the things I wasn't able to get right that, in a way, produced the scenario," he says, recalling his training in "technologies that determine the vicissitudes" even as they "offer parameters for the actions."

Elisabeth Caravella,

“Howto”, 2014.

F

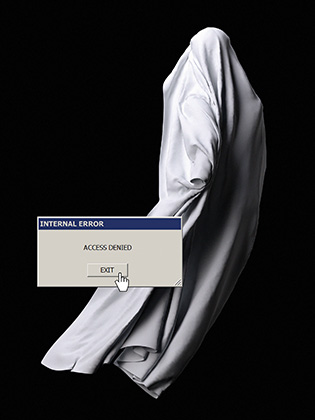

Following the advice of Robert Henke, aka Monolake (artist, software engineer and author of the digital audio application Ableton Live),

Élisabeth Caravella made a YouTube tutorial showing how to use a (fictional) program to generate 3D typographical characters. "I wanted to show that this isn't such a big deal," she tells us. That explains her choice of a "3D text, something that was very fashionable and back in the 1990s but is less so today," as an off-screen voice explains during her 2014 video Howto. Aware that "In tutorials, you don't see the person," she decided that her own ghostly presence, and sometimes nothing more, would haunt the video's setting, a former ballroom. In contrast to the digital coldness of her 3-D program, there looms a figure wrapped in a sheet whose fluidity could be a visual manifestation of a coding-bug, "a kind of poltergeist that can pop up in software beta versions." Or maybe the creature in her virtual reality version of this piece occupying Le Fresnoy's high ceilinged great hall is the ghost of a dancer out of the past who continues to haunt this site dedicated to learning and the appearance of the new.

Interface Magic

Atsunobu Kohira,

“Infravoice”, 2009.

N

Northern France, where Le Fresnoy is located, is rarely troubled by the seismic activity that too often rocks Japan, where the emerging artist

Atsunobu Kohira comes from. Like most of Le Fresnoy's residents, he previously attended another art school, in his case the Paris École Nationale des Beaux-arts. Newly arrived here, his piece for the 2009 student/teacher survey show Panorama was a stimulated earth-quake. He believes that "the Earth is alive," as if it were animated by a spirit. In his sound installation seeking to demonstrate that thesis, visitors communicate directly with the center of the Earth and their words are sent back in the form of vibrations. "Visitors' voices go through a cylinder buried in the ground and penetrate deeply into the Earth, like a pebble dropped into a well... These voices come back to the surface like an echo or a shock wave," he explains, confiding that the Fukushima disaster utterly changed his work and even his use of electricity.

Léonore Mercier,

“Le Damassama”,2011.

T

The use of technology in art makes it possible to bring objects alive and sometimes infuse them with a certain magic quality. This has been well-known to sound art practitioners since the time of the Italian and Russian avant-gardes, when Soviet citizen Leon Theremin invented the first hands-off musical instrument. Léonore Mercier has been following the same road since 2011, when she invented the Damassama, an instrument comprising Tibetan singing bowls arranged in an amphitheater. Visitors to the Panorama 13 (2011) exhibition were able to play it for themselves, and not badly at that. Playing the role of an orchestral conductor, they made the bowls ring by making hand gestures in their direction as if by telekinesis. This let them experience the invisibility of the space separating them from the instruments, which, despite the lack of instrumentalist, yielded sounds and music. Mercier's sound installations, nevertheless, are still sculptural and therefore highly spatial. Her latest instrument, the

Synesthesium, a dome some dozens meters wide equipped with a multitude of speakers, produces a total sound immersion.

David Rokeby,

"Hand-held", 2012,

production Le Fresnoy.

T

The Canadian

David Rokeby, an artist in residence/guest professor in 2011-12, worked with students and produced the piece presented at Panorama 14 (2012), marked by a relatively open exhibition design. Here, too, the question was invisibility, or, more precisely, he says, "the secret life of an empty space." There is not a single nook or cranny in France's cities and countryside that is not permanently bombarded with electromagnetic waves sent to or emitted by our connected devices. His installations Hand-held incites visitors to stick out their hand and snatch a few images from the piece's entirely empty space. Our gaze is drawn to our hands, covered with video-projected images activated by their motion. We don't really know what will happen until we walk through the space, devices in hand, and suddenly realize what lies beyond the screen, unable to ignore, without being worried by it, what's happening on some possibly distant server as we concentrate on what is, literally, at hand, as the rest of the world melts away.

Textualities

Lukas Truniger,

“Déjà Entendu

| An Opera Automaton”,

2015.

W

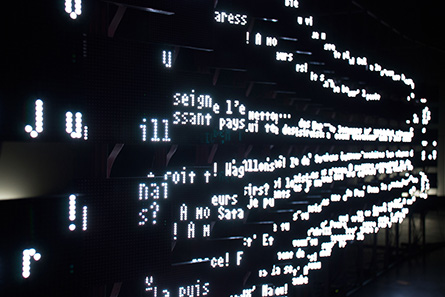

Works produced at Le Fresnoy are often shown abroad. This was the case with the audio and textual installation Déja Entendu | An Opera Automaton by the Swiss artist

Lukas Truniger. Made in 2015, it has already been presented in Paris, Issy-les-Moulineaux, Hong Kong and Montreal. This piece is more than the robotic opera that the title suggests. The machine in question, endowed with more than a hundred LED screens, has an undeniable stage presence. Its database has been supplied with lyrics and melodies of the main operas inspired by the myth of Faust. "The director Cyril Teste and I thoroughly discussed the issues involved in 'updating'aclassical opera," reports Truniger, who studied music as well as art and media. The result is a sound and word piece that demonstrates its point rather than telling us. It changes depending on one's point of view, what side of the stage one sits. The extraordinary quantity of wires coming out makes it look like a data center corridor. Faust's pact with the devil is paralleled by the contemporary "Terms and Conditions" we regularly accept without reading or knowing exactly hat we are agreeing to when we tick that box.

Fabien Zocco,

L'entreprise

de déconstruction

théotechnique,

2016.

“I

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." The Bible is the subject of the 2016 dramatic installation L'Entreprise de déconstruction théotechique by

Fabien Zocco, driven by a database stocked with all the words in the Old and New Testaments. (A side point: Zocco benefitted from advice by Arnaud Petit, the composer who worked on the sound elements of the seminal 1985 exhibition at the Pompidou Center curated by Thierry Chaput and Jean-François Lyotard, Les Immatériaux.) As Zocco recently described his work, "There is an artificial intelligence at work that deconstructs the whole Bible, word by word, and uses algorithms to recompose snatches of phrases in real time." Beyond the strange poetry spouted by mechanized cell phones, the idea was to provide the machine with a text of non-human origin. But in turning over so much of the workings of our society to machines, haven't we launched a process to our own exclusion? This is a question that artists who take up technologies that shape our world are grappling with.

Written by Dominique Moulon for Art Press and translated by

L-S Torgoff, July 2017.