JAPON, ART AND INNOVATION

by Dominique Moulon [ April 2016 ]

This year, the Japanese House of Culture in Paris has initiated a series of exhibitions titled Transphere. Named Fertile Landscapes, the first is dedicated to artists Daito Manabe and Motoi Ishibashi who often work together in the company they run, Rhizomatiks Research.

Fertile Landscapes

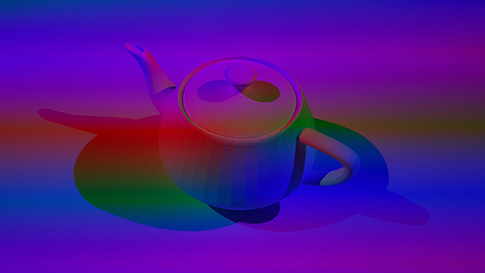

Daito Manabe

& Motoi Ishibashi,

“Rate-Shadow”,

2016.

I

I went to Tokyo for the first time in the early 2000’s, accompanied by images of Wim Wenders and the words of Roland Barthes. In the city, passers-by would be looking at their mobile phones while in France at the same time, we were still listening to them. I returned to Japan a few years later to meet with artists like Masaki Fujihata, Toshio Iwai and Seiko Mikami. I also exchanged with theoreticians, critics and curators such as Machiko Kusahara, Aomi Okabe and Yukiko Shikata during my travels around the world. It is said that globalisation is constantly undermining our cultural differences. Yet it is a trend in art to enhance the objects of varying technologies to infuse them with life to the point of lending them a soul, whose extremely localised geographical origins we know. Though this trend called device art does not embrace all the artistic practices of the country of the rising sun, it nevertheless symbolises the uninhibited relations between Japanese artists making use of the technologies of their time to create works of art.

Artificial facial expressions

Daito Manabe & Ei Wada,

“Face Visualizer”, 2011.

Daito Manabe

Daito Manabe is among those who, seizing all the emerging technological trends, innovates them into art. And like almost everyone, I found the film experience that propelled him to the front of the international scene on the Internet. Considered a simple test before becoming the performance Face Visualizer, which I had the chance to see in festivals like Transmediale in Berlin and Exit in Paris, this film continues to fascinate us with its strangeness. Having placed electrodes on the muscles of his face, the Japanese artist becomes enslaved to the minimal sounds of electronic music. This immoderate confidence in technological devices reminds us today of that which the exceptional English mathematician Alan Turing accorded machines in his time. And what about the workshops that Daito Manabe animates around the world, synchronising artificial facial expressions of one with the other? The ‘medium’ IS precisely ‘the message’ then, as the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan has taught us.

Particles

Daito Manabe

& Motoi Ishibashi,

“Particules”, 2011.

D

During the contemporary art festival Voyage à Nantes, I discovered the particles installation Daito Manabe designed and built with

Motoi Ishibashi. This installation, which combines sound flows with lights, carries on the traditions of the kinetic art of the 1960’s. It is the expression of a motorised art that coding artists now control by producing works that have been recently described as neo-kinetic. If there is a trend in digital art, it is that of a contemporary art practiced by artists documenting our society with the use of technologies that shape it. As for particles, which engages by the immediacy of our relationship to the work, it is adapted to very different interpretations for those who accord it more than a simple contemplation. It is important to note that the public has the opportunity to interact with the work, which earned it a distinction in interactive art at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria. In doing so, the most respected event dedicated to the arts, sciences, technology and social issues reveals one of the historical origins of emerging practices at the same time as it highlights the part technology plays in reviving it.

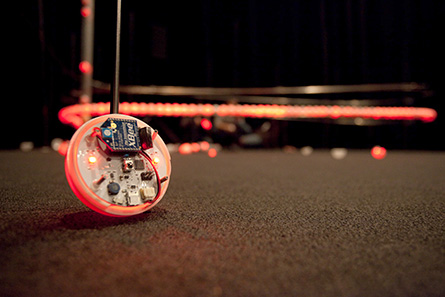

Art and robots

Daito Manabe

& Motoi Ishibashi,

“Pulse”, 2013.

L

Lastly, it was at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, during a meeting with Daito Manabe and Motoi Ishibashi as part of the Digital Week in Paris that I discovered their pulse performance, which synthesises many of our contemporary concerns. The relationship they establish on stage between humans and robots is in close resonance with the concerns of the French choreographer Aurélien Bory, because there are ideas floating around that regulate innovations. As for the drones that both artists contextualise again in the performing arts, it is their ability to communicate that they are testing, to exchange among themselves as with a body. And it is perhaps there, in the relationships that we have with each other through technical objects, communicating themselves among themselves, that the bulk of Daito Manabe’s and Motoi Ishibashi’s research is focused. Their work is thus at the frontier of artistic practices, technology innovation and societal issues.

Written by Dominique Moulon for the Japanese House of Culture in Paris and translated by Geoffrey Finch, April 2016.