SOUND ART @ ZKM, MAC & 104

by Dominique Moulon [ January 2013 ]

As far back as the early 1900’s, the Italian futurist Luigi Russolo foresaw sound as a medium by playing “noises” with the instrument he called an “Intonarumori”. Since then, numerous artists or sound artists have participated in what today is called Sound Art. Now art centres like ZKM in Karlsruhe, the MAC in Lyon and the Centquatre, in Paris, are echoing this artistic practice.

Taking over amateur practices

Cory Arcangel,

“Drei Klavierstücke

op. 11”, 2009.

A

Are there still any differences between the video practices of amateurs and professionals when we are all potentially directors of our own TV channel on the Internet? Have they arisen through intention, popularity or because of broadcast spaces? An entire life would not suffice to watch all of the sequences that show up when the word ‘cat’ is entered on You Tube! It was by doing such research that the American artist

Cory Arcangel collected amateur films documenting a few of the innumerable videos of cats stepping on piano and synthesiser keys. For anyone interested, he freely gives the name of the application that allowed him to organise the samples according to the notes of Arnold Schoenberg’s Opus 11 of three pieces for piano (“Drei Klavierstücke”, 1909). By doing this, he appropriates the accounts of ordinary people in order to glorify them in a museum. This practice of video sampling in the era of global sharing is once again a matter of relationship forms.

The synthesis of all of our fears

Tyler Adams

“Sirens”, 2012.

T

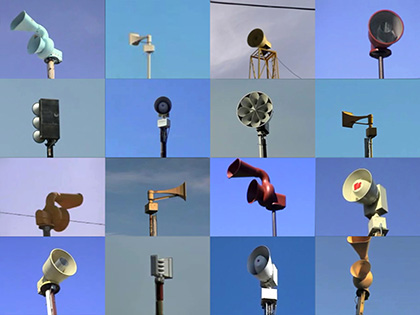

There is a siren for every catastrophe, industrial or natural, and children around the world who have never known war, hear the startling sound beginning deep and grave and becoming increasingly strident, most often the first Wednesday of every month, of a warning siren. Just within France there are several thousand, which we can easily imagine in the most diverse shapes and colours. It is precisely this diversity that is the focus of

Tyler Adams piece entitled “Sirens”, dating from 2012. He has brought together sixteen entirely different sirens in the frame of a video grid. But this choreography is menacing because it precedes the horror of our imaginings. By fusing the sound of many sirens, the artist plays upon all our associated fears. And we begin to think of the sirens that sounded during WWII, those that happily remained silent during the cold war and those that ring out today in Syria, Israel or in Gaza, because there is always a siren wailing somewhere in the world. And in general, all they have for echo are the silences of those who live in peace.

Chronicle of a death foretold

Christian Marclay,

“Guitar Drag”, 2000,

Courtesy Paula Cooper.

Christian Marclay

Christian Marclay’s gestures in the film “Guitar Drag” are measured. Without any great haste, he attaches a Fender Stratocaster by its neck to a Pick-Up that he then starts up. It is when its foretold destruction begins that the final solo is drawn out right to its end - an endless moan. And there is the sound along the way that is even more chaotic. The work comes to an end when the amplifier no longer has anything more to amplify. The concert ends and we inevitably think of Pete Townshend for whom trashing his guitars on the ground to extract their final sounds became a habit, or Nam June Paik in a more gentle mode, dragging a violin behind him. Unless we think of the horror of the racist crimes that involve dragging men, for the colour of their skins, behind trucks as was the case in Texas as recently as 1998. But the violence in Christian Marclay’s film dating from 2000 is situated more in the preparation when the sentence that has been pronounced is comparable to the ceremony that precedes an execution in the corridors of a death foretold.

The plasticity of silence

Douglas Henderson,

“Stop”, 2007.

T

There is another electric guitar at the ZKM, which was silenced when the artist

Douglas Henderson buried it in a block of concrete. The work “Stop”, dating from 2007 could be thought of as another homage to the 4’33’’ of silence that John Cage composed in 1952. No sound will ever be heard again from this guitar in the Media Museum, frozen in time like everything was in Pompei in the year 79. The Marshall amplifier to which the guitar is connected reveals only its potential. This art work in the exhibition participates in pushing the limits of sonic art as far as sculpture where sound figures only by its absence, its lack. The block of concrete preserves the work by depriving the instrument of its primary function. But is not the primary function of a museum to preserve? Beyond its obvious plasticity, “Stop” is a work that is open to many interpretations as it might just as well symbolise those we reduce to silence, or those who find themselves confined within four concrete walls when their ideas offend. The question of musicality is decidedly absent.

Correspondences

Edwin van der Heide,

“Sound Modulated Light 3”,

2004-2007.

T

To experience

Edwin van der Heide’s sound installation, one must first be equipped with an audio headset that is linked to a photo-sensitive sensor as the quality of the light emitted by “Sound Modulated Light” varies from one bulb to another. By holding an electronic sensor in the hand, we can look for the sounds corresponding to the different light signals. What we hear is nothing other than what we see and so we are particularly attentive to the environment around us, like photographers peering through their lenses. We then look for the sounds that are hidden in the ambient light of the sensor that defines the scope of the work. At the exit, those who haven’t taken off their headset will perceive that the screen of the video work adjacent to “Sound Modulated Light” also emits its own audio signal. The world around us is thus filled with sound messages that are only waiting for us to hear them. Beyond the game of discovering sounds hidden in space ‘by hand’, Edwin van der Heide’s light installation incites us to better hear the world, which is too often masked by seeing.

Our resonating bodies

Kaffe Matthews,

“Sonic Bed”. 2005,

photo Colin Mearns

T

The artist

Kaffe Matthews asks the public to take off their shoes before lying down on her “Sonic Bed”, which looks slightly like a coffin for three (or four) people. It is equipped with an entirely invisible sound installation that might make certain amateurs of tuning green with envy. Lying down comfortably, one must totally abandon mind and body for the experience to be complete. Bodies complete the work by resonating frequencies that are played by it. Laying on this sonic bed amounts to listening to one’s body via the sounds that pass through it, as there are sounds, frequencies that are among the lowest, that are heard from within, through our skeletons and right through our flesh. The sensorial experience of “Sonic Bed” can be shared by two, three or four participants even if the sound journeys one makes are resolutely personal. Once again, this exhibition, organised by Peter Weibel, the director of the ZKM, and Julia Gerlach, incite us to listen to the sounds of the world around us differently.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon

La Monte Young

& Marian Zazeela,

“Dream House”, 2012,

photo Blaise Adilon.

O

One must take one’s shoes off again before entering the “Dream House” that the

Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon has reactivated in 2012 after initially exhibiting it in 1999. But it was at the beginning of the 1990’s that the National Fund for Contemporary Art acquired it from the Jacques Donguy Gallery, whereas La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela conceived their first sound and light installations in the 1960’s. The moderator at the entrance, bizarrely, is wearing protective headphones. Is this what he needs to prevent himself from really letting go? As for the spectators, they easily let themselves go by becoming one with the sound and light matter of the installation. There are those who move around to interact with the sound of this space, favourable to modified states of consciousness while others sit down, or lie down on the floor of this environment whose interior is uniformly painted pink. Eyes are open or closed and spirits are here and now in this experience of a moment.

At the Centquatre

Zimoun, “416 prepared

dc-motors, hemp cords,

cardboard boxes

60x60x60cm”, 2012.

L

Lastly, at the

Centquatre, there is an installation of apparent complexity whose name included the components implemented in the work: “416 prepared dc-motors, hemp cords, cardboard boxes 60x60x60cm”. From the outside, the work looks like a monumental sculpture whose material, which is cardboard, betrays its fragility. From the inside, we hear a sound that is comparable to that of driving rain. And within, one strains to focus on anything as the structure is uniformly animated by micro-movements. The architectural shape that rises upward is minimalist whereas the movements are so chaotic that they manage to combine into one sound, which is practically like white noise. One could say it’s like the sound of a soothing fountain, and it is a kind of fountain the Swiss artist has installed at the Centquatre. The 416 motors when independent of one another are entirely without interest. But it is by combining them together that they make sense all together. Much like Felix Gonzales Torres blue candies. As for the kinetic aspect of

Zimoun’s work, it has not escaped the notice of the

Denise René Gallery who have only recently come to represent him in France.

Written by Dominique Moulon for Digitalarti and translated by Geoffrey Finch, January 2013.