ZKM, TRANSMEDIALE, IKEDA AND BARTHOLL

by Dominique Moulon [ April 2012 ]

At ZKM in Karlsruhe, the exhibition "The Global Contemporary" recently analysed the effects of globalisation on the world of art while that of the Media Museum, entitled "Digital Art Works", addressed the conservation of digital works. The Transmediale Festival in Berlin meanwhile just celebrated its twenty-fifth year of existence with the exhibition "in/compatible". Last but not least, Bartholl exhibited at the Dam Gallery and Ryoji Ikeda at the Hamburger Bahnhof.

Art and finance

T

The exhibition "The Global Contemporary" begins right at the entrance of the

Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM). The words "SELL" and "BUY" immediately incite one to enter PanoramaLabor. The space looks like a control room. Yet the artists of the

RYbN project who conceived this installation don't control anything because the bot they launched on the Internet in August 2011 is entirely autonomous. "ADM8", is its name and it was given 8,279 Euros to invest, as it is capable of buying and selling on Asian, European and American financial markets. The huge amount of information it collects enables it to anticipate the movements of the market so it can endure as long as possible. But it will eventually fail when its counter reaches zero. This work, which we might consider today as unfinished, will then be finished. With PanoramaLabor, whose circular wall is entirely covered with maps, tables and numbers, indications of this robot trader's actions, we only observe its slow agony. It has been predicted that it will take it a few years before it makes the fatal, final transaction, so it will take time. The world of high finance is unforgiving with machine errors, but what about non-machine errors?

Adding value

Laurent Mignonneau

and Christa Sommerer,

"The Value of Art", 2010.

“T

“The Global Contemporary" theme carries on in the ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art where the installation "The Value of Art" draws attention. It focuses on a painting that was purchased for 425 Euros by

Laurent Mignonneau and Christa Sommerer at an auction in Vienna. The artists have added a sensing device and a thermal printer. They then awarded a value for the time spent by viewers of the painting at one euro per ten seconds. It is thus the spectator that determines the value of the work and not the market. Only their attention is taken into account by the device, which is added to that of the previous viewer. The length of the roll of paper coming out of the printer shows the success of the seascape signed by a certain Hansen. Everyone can check that the time they've spent looking at the work has been taken into account and that they have participated in increasing the value of a decidedly autonomous work, as it cuts out merchants, collectors and critics who ordinarily set the value of art. It is an alternative economy that Laurent Mignonneau and Christa Sommerer describe as "an economy of attention".

Conservation

Nicolas Moulin,

"Viderparis",

2002.

W

We next go to the Media Museum where the exhibition "Digital Art Works - The Challenges of Conservation" brings together digital works whose case studies are based on their respective durability, there where urban landscapes follow one upon the other. The length of time for each is similar, the order random and the sound rather agonising. All of them bear the same strangeness, which we only observe a little after the fact. The time it takes to realise that the artist, Nicolas Moulin, has erased all forms and traces of existence, whatever they might be. All that remains in "Viderparis" are buildings whose ground floors have been walled up. The uncluttered perspectives are comparable to the representations of ideal cities dating from the Renaissance. Were they ever inhabited and who could possibly tell us when there's absolutely no one there? The boulevards and avenues were evacuated slowly and without rushing, since nothing has been forgotten in contrast to scenes of the aftermath of catastrophes. The durability of "Viderparis" seems to us to be assured as long as there are applications that can randomly show image and sound files, unless of course there is a real catastrophe.

The aesthetics of risk

Ben Woodeson,

"Health & Safety

Violation #36", 2012.

I

It is in the bleak mid winter of Berlin that the

Transmediale festival takes over the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. In the centre of the main foyer there is an alignment of copper wires that is relatively sculptural. It is a sculpture that one might describe as minimal before testing it. As its title indicates "Health & Safety Violation #36", it belongs to a series that its author,

Ben Woodeson, started in December 2008 at a time when he was feeling uninspired. Designing dangerous works took him out of his torpor and found him writing disclaimers that the public must sign. The one you have to sign in Berlin covers the place, the event and the artist so one can go ahead and freely electrocute oneself. Because it is indeed what this is about: having the courage, or the rashness to take hold of two highly electrically conductive copper wires. The consecutive movements of pulling away from the short-term electric shock are vigorous and we are told that it is lovers of artistic shocks who repeat the experience. And because it is often interactive works that offer spectacles when taken over by the public, the armchairs located close to this electrifying work are never empty.

Amateur practices

Eva & Franco Mattes,

"My Generation", 2010.

T

This year, amateur practices are much in evidence at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. For example, the author on the card that accompanies the video sequence of the CEO of Microsoft, Steve Balmer, publicly asserting his extreme attachment to his company is anonymous. It should be noted though that it is also accessible via Google by entering "Steve Ballmer going crazy" and has more than four million hits to date. As for the video collage "RIP in pieces America", which draws a bitter portrait of the United States in the era of YouTube, it gathers sequences that the Canadian, Dominic Gagnon kept before they were removed from the web hosts because they were disturbing. Lastly, the, installation "My Generation" by the artists

Eva et Franco Mattes feature sequences that are also all made by amateurs, but that are all accessible on the Internet. Together they create a portrait of a youth that puts absolutely everything into video games and other communities such as 'World of Warcraft'. So far, there have been sixty million hits for "Greatest freak out ever". For every passing minute there is an additional sixty hours of video added to YouTube. But how many declarations, suppressions or collages of amateur video practitioners will curators and artists of their own time validate?

At the CTM Festival

Anke Eckardt,

"Between I you I and I me",

2011,

source Marco Microbi.

T

Transmediale continues in the Kreuzberg quarter at the

CTM, its traditional partner and it's at the Bethanien that

Anke Eckardt presents her installation entitled "Between I you I and I me". The title here again informs us about the work, which, according to the artist, is nothing other than a "wall of sound and light". The room is in the dark and full of vapour so that two rays of light projected to form membranes invite us to penetrate them with our hands. This double immaterial wall must be crossed for the experience to be complete. But what is on the other side? The spectators take their time and generally begin by putting their hand through and then their arm. Between the two films of vapour we hear piercing sounds of glass breaking, evoking the sound of breaking through a glass partition. The world is similar on the other side. This work is as radiant in its fragility as it is rich in possible metaphor when one considers the barriers the powerful erect between the most fragile. Because there are indeed barriers that each one of us must cross and "Between I you I and I me" encourage us to do so. Here the result of clearing barriers is an aesthetic pleasure.

At the DAM Gallery

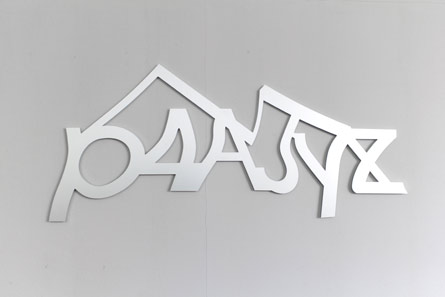

Aram Bartholl,

"Are you human?",

2009.

T

There is an exhibition by

Aram Bartholl, one of the most digital of all artists, at the

Dam Gallery in Berlin. But here he presents works that are clearly less digital than their inspiration. In particular, we find a few aluminium captchas from the series "Are You Human?" that look exactly like the typographic assemblages that machines impose for us to decipher to prove our humanity. Because that is where we are. CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) refer to the test that Alan Turing described in 1950 in his work "Computing machinery and intelligence". The objective of the protocol at the time, which had to be followed by a human, was to distinguish a man or a woman from a machine. But now, sixty years later, it is machines that interrogate us. Aram Bartholl sometimes puts his captchas up in urban spaces. When they're not being confused with graffiti, two existential questions emerge: Where am I and who am I? Because we are in the face of these atrophied characters as close as we can get to the machines that question us.

At the Hamburger Bahnhof

Ryoji Ikeda,

"db", 2012,

source Uwe Walter,

courtesy Freunde

Guter Musik Berlin.

T

The last exhibition of the series "Works of Music by Visual Artists" presented at the

Hamburger Bahnhof was reserved for

Ryoji Ikeda. The museum gave him two symmetrical rooms of the East and West wings that the artist used for a work whose title, "db" for decibel, itself evokes symmetry - the double between complementarities and completeness. We are familiar with this Paris based Japanese artist's attachment for data. And what a pleasure in following the path that leads to the West room to look at one of the numbers that range between 2,289,862 and 2,307,403 painted by Roman Opalka in 1977. But lets return to 2012 and go into the West room that Ryoji Ikeda has converted into an immaculate space from floor to ceiling. We are immediately blinded by the extreme whiteness that resembles that of the suite where Dave's quest ends in "2001, A Space Odyssey". So we let go completely when the work slows our movements in space and the pure sound coming from the depths of the room draws us ineluctably. All around there is data, coming from we don't know where - perhaps the frontiers of space… And then, there is the second room, its double black with a beam of white light and again data, numbers. Roman Opalka died last year, but there are still artists like Ryoji Ikeda to slow time down.

Written by Dominique Moulon for Digitalarti and translated by Geoffrey Finch, April 2012.